Telling stories is hands-down the most effective way to communicate. But there’s a big difference between bad storytelling and good storytelling. Simply going through the motions isn’t going to result in creating the remarkable content you need in order to be effective. In this post, I’m going to show you the mechanics of storytelling and give you three frameworks you can use in order to make your activism the most effective it can be.

Intro

“It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.”

Now, that was an example of bad storytelling, so much so that it’s become a cliche and a punchline. But that doesn’t stop politicians, bloggers, and journalists from using that same approach in their content. I think there are two reasons why. The first is that people honestly don’t know any better. They’ve been told a million times that telling stories is the most effective way to connect with other people. And so they mimic what they’ve read in novels or seen in movies, which is a perfectly logical thing to do and it doesn’t bother me. The second reason, however, does bother me because it’s a group of people who should know better and I’m talking about journalists. I think a lot of the journalists who fall into this trap are really frustrated novelists and they think of themselves as an Ernest Hemmingway who just hasn’t been discovered yet.

Here’s the problem with writing a blog post or an editorial a video script like it’s a novel or a movie: You’re not writing a novel or filming a movie! You’re not even writing a short story. You’re creating a piece of content that needs to grab people’s attention quickly, keep that attention as long as possible, and make a point in a clear and compelling way.

I get really frustrated reading a lot of news stories these days. The opening paragraphs are really just weak attempts at repackaging the old, “It was a dark and stormy night.” I know what they’re trying to do but I just don’t have the time for their amateur auditions for an Emerging Novelist of the Year award. I just want the information and I want to get on with my life.

So if that’s the wrong approach, what’s the right approach? Well, that’s what we’re going to cover in this article. I’ll talk about some of the fundamental structures of storytelling, give you three frameworks that will set you up for success with your content, and then leave you with a few resources and recommended reading if you want to learn more.

Framework 1: The Hero’s Journey

I’ve read a lot of books about storytelling and honestly, I found that the most popular and recommended ones didn’t really help me. I think it’s because, again, they’re more focused on long-form storytelling than the kind of short-form persuasion that activists need to master. Ironically, the book that taught me the most was the longest book on the subject and was singularly focused on screenwriting. That might sound like it contradicts some of my earlier statements but I’ll explain why.

The book is simply titled Story and it’s by Robert McKee. McKee is a legend in Hollywood and has been running very popular screenwriting workshops for decades. The subtitle is “Substance, Structure, Style, and Principles of Screenwriting.” Maybe it’s the engineer in me or maybe it’s because I’m old enough to have gone to school when they still diagrammed sentences. But this book really appealed to me because it is essentially diagramming movies the same way you’d diagram a sentence. And if you’re a movie enthusiast, I highly recommend getting this book because number one, you’ll find it fascinating and number two, you’ll never be able to watch a movie ever again without breaking it down into its building blocks.

It’s a long book, so I can really just cover the very fundamentals here.

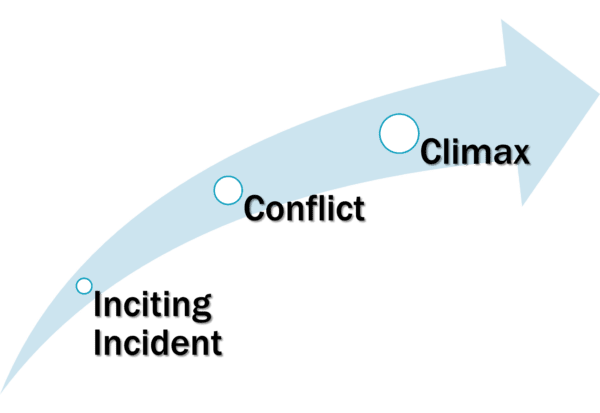

The Inciting Incident

Every story has an inciting incident that “radically upsets the balance of forces in the protagonist’s life.” The remainder of the story is a quest to restore that balance.

Conflict

A story is divided into acts, which are punctuated by conflict. These conflicts can be either positive or negative and will typically alternate throughout the story.

Climax

Finally, the story ends once balance is restored one way or another. It doesn’t mean that things returned to the way they were at the beginning of the story. As McKee puts it, the climax is “A revolution in values from positive to negative or negative to positive with or without irony – a value swing at maximum charge that’s absolute and irreversible.” And in Aristotle’s words, an ending must be both “inevitable and unexpected.”

This structure is also known as The Hero’s Journey or the Three-Act Play. There have been thousands of books written about it because it works. However, there’s a problem with trying to implement this framework in the realm of digital content. And that problem is attention and competition.

There’s fierce competition for the attention of your audience. I don’t need to explain how bombarded we all our these days with emails, social media posts, videos, etc. You generally don’t have the luxury of getting people to sit through your three-act play or your hero’s journey.

And this is the problem I have with many journalists these days – the ones I made fun of at the beginning of this post. I get the feeling they imagine themselves as the next Stephen King or Kurt Vonnegut. They’re overconfident in their writing skills and think they can hypnotize you with their prose and draw you into their story. In my opinion, what they’re really doing is wasting and disrespecting your time. You’re generally not kicking back on the couch with a bowl of popcorn and settling in to read a Russian novel about the latest unemployment figures. You want the facts and even more importantly, you want to understand what they mean. And you don’t want to give up ten minutes of your life before you know whether or not the payoff is going to be there.

Fortunately, there’s a technique you can use to structure your content in a way that leverages storytelling in a much more direct, efficient manner.

Framework 2: The Human Action Model

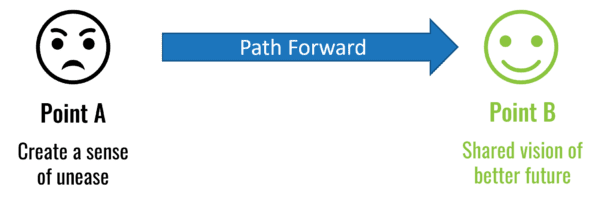

The Human Action Model is something every activist should be familiar with. It also happens to be my personal favorite and go-to framework for crafting content. It’s derived from Human Action: A Treatise on Economics by the Austrian economist and philosopher Ludwig von Mises. It states that human action is guided by self-interest in pursuit of a state superior to the status quo. It’s a bit of a twist on the hero’s journey and perfectly suited for activism because it leverages storytelling to create action.

The Human Action model has three key components:

- A sense of unease

- A shared vision of a better future

- A path to get there

When you break this down, it’s actually mind-blowingly simple. Another way to think about this is a straightforward journey from point A to point B. Your audience is currently sitting at point A but they don’t want to be. That’s the sense of unease you want to aggravate. Point B is where they would rather be. That’s the better future you need to articulate. And then you need to provide them with a path to get there.

At this point, I want to share an example with you. And the example we’ll use is this article you’re reading right now. Let’s go back to the opening and deconstruct it, sentence by sentence.

“Telling stories is hands-down the most effective way to communicate. But there’s a big difference between bad storytelling and good storytelling.” That’s point A. I’ve created a sense of unease by making you wonder if you know what good storytelling is.

“Simply going through the motions isn’t going to result in creating the remarkable content you need in order to be effective.” That’s point B. I’ve created a vision that probably appealed to you because you want to be effective in your mission.

“In this article, I’m going to show you the mechanics of storytelling and give you three frameworks you can use to make your activism the most effective it can be.” That’s the path forward. It’s also a promise to you: In the first few seconds of the post, I’ve planted a desire in your brain and then promised to give you a roadmap to achieving that desire.

As I mentioned earlier, this is my go-to technique for creating content but it actually has even more broad applications. I think it’s a great tool for branding and establishing your core messaging. I’m a big fan of defining vision, mission, and value statements for your campaign or your cause. The human action model is a great tool for developing those, in my opinion. It can also be used to develop your stump speech and there’s even a miniaturized version of it that I use for scripting one-minute videos.

I really can’t emphasize enough how useful this has been in my marketing and activism.

Framework 3: The Public Narrative

The Public Narrative Framework was created by Marshall Ganz of Harvard University to help explain how to lead social change. As Ganz puts it, “Mobilizing others to achieve purpose under conditions of uncertainty–what leaders do–challenges the hands, the head, and the heart.” In order to accomplish this mobilization, the framework weaves together three stories into a single narrative.

The first is is the story of self. It answers the question, “Why me?” Why were you personally called to this mission? Here, you want to tell the story of how and why you were moved to take action.

The second is the Story of Us. It answers the question, “Why are we called?” In this story, you want to focus on the shared values that identify the people in your tribe who will find common purpose with your movement.

Finally, the third is the Story of Now. It answers the question, “Why now?” This establishes urgency. While the first two stories are designed to stir emotions and create a sense of community, this final story is a call to action. It should motivate people who identified with the first two stories to actually take action and join your movement.

And so the public narrative is actually a combination of three specific kinds of stories that are designed to elicit an emotional response and then motivate people to take action. You can lean on the two previous frameworks for creating these three stories.

Conclusion

So there you have it – three storytelling frameworks you can use to make your digital activism content more compelling and persuasive. There’s the traditional hero’s journey that’s utilized in novels and movies. In most cases, I don’t think it works particularly well for the kinds of short-form content you’re probably going to be creating. Then there’s that human action model, which I think is one of the most powerful tools available to anyone creating content, whether they’re trying to affect social change or selling products or services. Not only does it work really well, it’s dead simple to understand and deploy. Finally, there’s the public narrative that combines three separate stories into a single narrative to help recruit, motivate, and mobilize other activists.

There’s an old Native American proverb that I love. “Tell me the facts and I’ll learn. Tell me the truth and I’ll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.” Let me tell you, as a recovering engineer, this is something that took me a long, long time to realize. In fact, social media helped me realize the power of storytelling and inspired me to write my book. The title that I wanted for the book was “The Right-Brain Handbook,” because it helped right-brained people like me understand that we need left-brain skills to thrive in this digital age. But my publisher insisted that we call it something much more descriptive and so it became “Social Media for Engineers and Scientists.” Not very inspiring but they called those shots.

I think we see a lot of the same problems with activists and politicians who don’t understand the art of persuasion. They think that facts are how people make decisions but that’s not how it works. Facts are things we use to rationalize our decisions after they’re already made. Decisions aren’t made by the frontal cortex, they’re made in the emotional center of our brain. If you want to tap into you’ve simply got to tell stories. I hope this helped you learn the importance of storytelling and gave you some actionable tips to make it an integral part of your activism.